6 things You Need To Know About The Klamath River Dam Removals

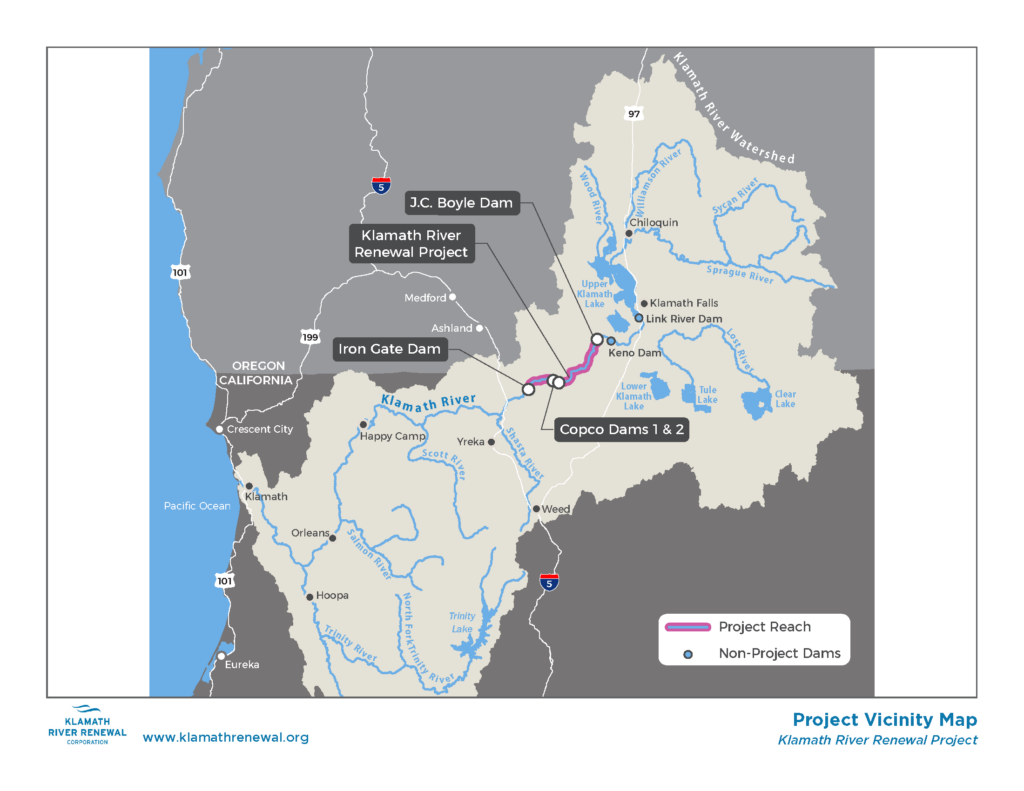

For nearly 100 years, dams on the Klamath River have blocked salmon and steelhead from reaching more than 400 miles of habitat, encroached on indigenous culture, and harmed water quality for people and wildlife. The time has finally come for the four dams – J.C. Boyle, Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, and Iron Gate – built between 1908 and 1962, to come down. This river restoration project will have lasting benefits for the river, salmon, and communities throughout the Klamath Basin. Here are 6 things you need to know about the Klamath River Dam Removals.

- One of the largest dam removals in world history

Four dams along the Klamath River, which runs from Oregon into northwestern California, are scheduled to be removed in 2023 and 2024 – Copco No. 1, Copco No. 2, Iron Gate, and JC Boyle. These dams total 400 vertical feet and choke fish passage along hundreds of miles of waterways, making this a historic opportunity and one of the largest dam removal projects to date. And construction has started! American Rivers is working in partnership with tribal nations, NGOs, the state and federal government and local stakeholders to ensure the health of the Klamath Rivers and the communities that depend on its vitality.

- Tribal advocacy created this opportunity

Tribal nations whose ancestral lands and histories have intersected with the Klamath watershed for thousands of years – including the Hoopa Valley, Yurok, and Karuk tribes – have spearheaded the collective effort to remove the Klamath dams. The health of the Klamath is a key facet of these peoples’ history, culture, and sustenance, and tribal leadership and perspective has profoundly shaped the course of events on the Klamath over the past two decades. Tribally-led advocacy included a high-profile protest when Berkshire Hathaway and PacifiCorp executives visited the Klamath in 2020. River advocates, led by the tribal nations, pushed the executives to join the effort to remove the Klamath dams.

- Many years, many players, many obstacles

Dam removal is far from a linear process, and the journey to get to the key milestone of removal began over 20 years ago. After a series of legal conflicts amongst stakeholders in the Klamath basin in 2001 and a catastrophic fish kill that resulted in the death of nearly 70,000 adult salmon in the Klamath River in 2002, different parties began working together collaboratively to address the health of the Klamath River and its communities and the movement towards dam removal began to gain momentum. Discussions around a far-ranging restoration plan in the Klamath basin began in 2005, with a proposed plan introduced to Congress in 2010, but the initial legislation failed to pass through Congress. A new piece of legislation, the Klamath Hydroelectric Settlement Agreement (KHSA) was signed into law by Congress in 2016, mandating the removal of the four Klamath dams within a broader push to restore riparian zones in the Klamath watershed. The Klamath River Renewal Corporation (a group appointed by the States of California and Oregon, local governments, Tribal nations, PacifiCorp (who owned the dams), irrigators, conservation and fishing groups), was tasked with taking ownership of the hydroelectric dams and managing their decommissioning and removal.

- Creating ecological resilience

Removing the Klamath dams promises a wide range of ecosystem benefits that enhance regional climate resilience and aid the imperiled salmonid populations that once surged into the watershed from the ocean (now only 5% of historic averages). Significantly, dam removal expands coldwater habitat for fish. Damming on the Klamath has contributed to raised water temperatures, leading to toxic algae blooms and decreased dissolved oxygen in the water, threatening the spawning grounds that salmon depend on for reproduction. By removing these four dams, we can help bring salmonid populations back from the brink, while restoring habitat for other species. Restoration doesn’t end with the removal of the dams. The plannet post-removal restoration includes expanded habitat for migratory birds travelling along the Pacific Flyway, as well as the other flora and fauna that depend on healthy rivers to thrive. Land that was formerly inundated in reservoirs will be revegetated with native plant species following dam removal through the dispersal of millions of seeds, providing ecologically vital riparian habitat.

- Strengthening communities through dam removal

The project itself has the potential to create hundreds of local jobs as we work collaboratively to remove the dams and conduct post-removal restoration along the river. The project is also cost-effective, ultimately saving money for ratepayers in the region over time, all while opening up recreation opportunities for the public. In the long-term, the dam removals are projected to reduce spending on disaster relief and the benefits to salmon will translate into economic benefits for the fisheries that depend on yearly runs up the Klamath. All of this points to healthier communities within the watershed, and a more sustainable regional economy.

- Key Dates to Know

July 2023 – The removal of Copco No. 2 begins.

August 2023 – Fish passage restored at Copco No. 2. Copco No. 2’s reservoir drained to allow for riparian habitat restoration post-removal.

September 2023 – Removal of powerhouse, penstocks, and residential buildings at Copco No. 2.

December 2023 – Drawdown of JC Boyle, Iron Gate, and Copco No. 1 (water levels lowered on reservoirs to enable construction activities)