Planning for Salmon and Steelhead to Return as the Klamath Dams Come Down

As the largest river restoration effort in history moves forward, Oregon and California plan for fish reintroduction and monitoring

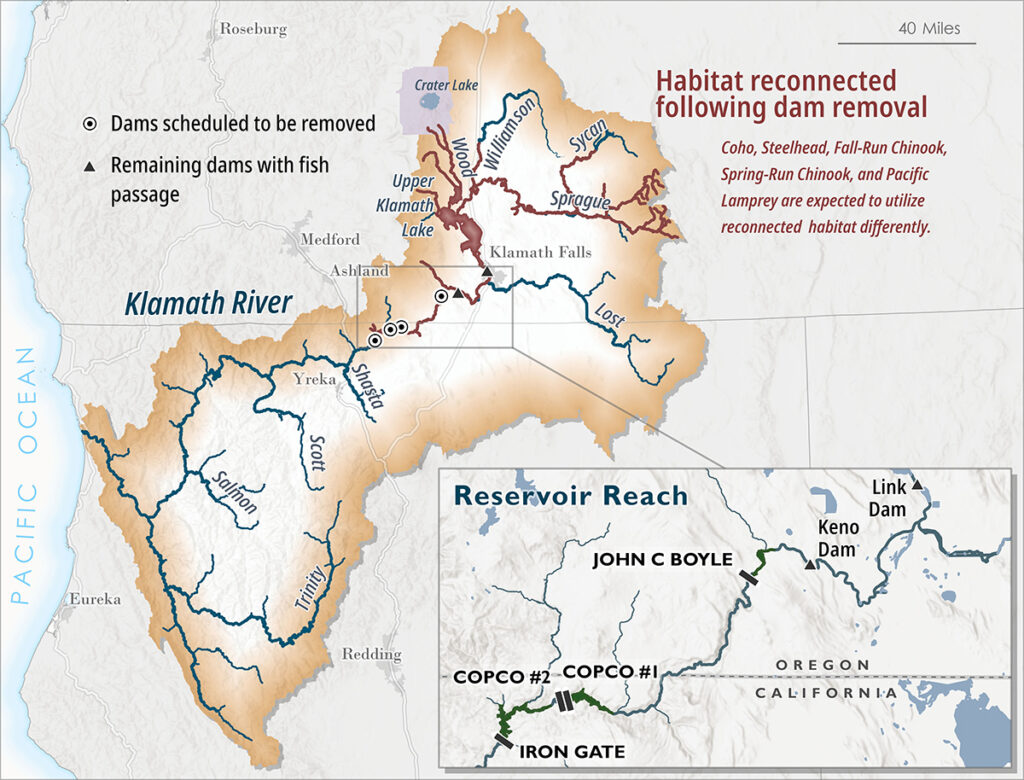

After decades of determined advocacy, tribes and conservation partners are now on the precipice of removing the four dams of the Klamath River Hydroelectric Project. For over a century, these dams have degraded water quality and blocked salmon, steelhead, and Pacific lamprey from migrating upstream, completely extirpating these native fish from over 400 miles of spawning and rearing habitat in southern Oregon and northern California.

Crews are about to prepare access roads and other infrastructure to receive the extensive equipment required to physically remove the dams. By Halloween, the smallest of the four dams, Copco 2, will be gone. The reservoirs behind JC Boyle, Copco No. 1, and Iron Gate dams will be drained next winter. Those three remaining dams are scheduled for removal starting in summer 2024. Taken together, this work comprises the largest dam removal in history.

While this phase of the project brings a lot of justified excitement, it is also time to prepare in earnest for the return of anadromous fishes upstream of Iron Gate Dam. Wild salmon, steelhead, and lamprey populations are only a small fraction of the size they were prior to dam construction. Removing the dams is the best opportunity to rebuild their numbers. Multiple regional plans are being developed to guide this restoration process.

TU has been at the forefront of the effort to prepare for the return of native fishes to the upper Klamath basin. Staff working in the basin partnered with NOAA Restoration Center and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission (PSMFC) to develop the Reservoir Reach Restoration Prioritization Plan to identify and prioritize key restoration projects in the inter-dam reach. This document will facilitate high-impact habitat restoration, fish screening and flow restoration projects in the portion of the watershed returning fish are most likely to first repopulate following dam removal.

Additionally, TU staff contributed to the Implementation Plan for the Reintroduction of Anadromous Fishes into the Oregon Portion of the Upper Klamath Basin developed by the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and The Klamath Tribes. The plan was completed in 2021 and will guide reintroduction efforts in Oregon’s portion of the upper watershed.

The California Natural Resources Agency and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) are currently working on the final version of their Klamath River Anadromous Fishery Reintroduction and Restoration Monitoring Plan, which will guide reintroduction in California’s portion of the lower watershed.

There are other plans in place for various restoration efforts throughout the Klamath basin including plans from both the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (USFWS) and the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, but this article focuses on the Oregon and California state plans because they are the primary roadmaps guiding fish reintroduction and monitoring efforts following dam removal.

ODFW and Klamath Tribes Reintroduction Plan

The Oregon reintroduction plan will primarily rely on fish naturally returning to the reconnected historic habitat in the upper basin. Fall-run Chinook, coho, steelhead, and lamprey are expected to utilize habitat in the reservoir reach as well as habitat upstream of Upper Klamath Lake once the dams are removed. Each species will be given three generations (9-15 years, depending on the species) to volitionally repopulate the upper Klamath before the Oregon plan would consider more active interventions, such as hatchery support.

The reintroduction of spring-run Chinook is expected to require a more involved approach. Spring-run Chinook are currently only found in the lower Klamath tributaries of the Trinity and Salmon rivers and would have to stray a minimum of 190 miles upstream to return to their historic habitat. Because of this distance and their small population sizes, ODFW and the Klamath Tribes plan to reintroduce spring-run Chinook using a conservation hatchery program with broodstock from the Trinity River.

Initially, 10,000-50,000 smolts and/or sub-yearlings will be released in portions of the upper watershed with year-round rearing habitat, such as the Wood River, Williamson River, North Fork Sprague River, and their tributaries. Their movement behavior, survival, health, and migration success will be monitored for 4-8 years, and then releases will be increased to >100,000 annually, with the intent of repopulating the upper basin to harvestable levels. Once a self-sustaining run is established, the Oregon plan anticipates that the hatchery program will sunset.

California Reintroduction Plan

The draft California reintroduction plan will rely on spring-run Chinook, steelhead, and lamprey volitionally returning to the former reservoir sites in California. CDFW and partners will continue hatchery programs for fall-run Chinook and coho. Hatchery production will move from the Iron Gate Hatchery to the Fall Creek Hatchery, which is being updated because Iron Gate Hatchery will be dismantled as a part of dam removal.

Hatchery releases of fall-run Chinook will continue to support subsistence and commercial fishing during the dam removals and reintroduction process, however annual juvenile releases will decrease from 6 million to 3.25 million. The coho conservation hatchery will continue annual releases of 75,000 juveniles while the population rebuilds from perilously low numbers. Biologists expect that both species will begin to naturally rebuild their numbers after regaining access to historic habitat following dam removal, and as such, the hatchery releases are only planned for up to eight years.

Upper Klamath Monitoring

Tracking Fish Populations After Dam Removal

Currently, much of the fish population monitoring in the lower Klamath is focused on juvenile and spawner abundances downstream of Iron Gate Dam. In the upper Klamath, the focus is on the ecology and restoration of C’waam and koptu (Lost River and shortnose suckers), redband and bull trout. When the dams come down, monitoring efforts will expand to new geographies and species as Chinook, coho, steelhead, and lamprey once again access their historic habitats.

Immediately after dam removal, planned monitoring efforts in both Oregon and California will primarily focus on the presence/absence of fishes in the “reservoir reach,” under the assumption that returning fish will return to this section of the watershed first before moving upstream of Link Dam and Upper Klamath Lake.

As time goes on, state and tribal scientists are planning to add additional monitoring to document spatial distribution and population productivity of anadromous fishes in the upper Klamath Basin. A wide variety of monitoring methods are in the plans, including PIT, radio, and acoustic tags, redd and carcass surveys, eDNA, video weirs, sonar, and juvenile-migrant traps. Scientists in the upper Klamath will coordinate their monitoring activities with monitoring in the lower river conducted by the Karuk Tribe, Yurok Tribe, USFWS, and others.

Upper Klamath Monitoring

The Importance of Funding the Reintroduction and Monitoring Plans

The dam removals in the Klamath River present an unprecedented opportunity to observe what can happen when anadromous fish regain access to hundreds of miles of high-quality habitat. The California and Oregon Plans are the road map for Klamath fish reintroduction, and monitoring is a key component of that process. Without it, we would be embarking upon the largest river restoration project in recorded history without knowing how fish populations are responding or whether there are actions managers could take to improve their success. Investing in the recommended, comprehensive monitoring, beginning immediately after dam removal, is critical to ensuring the investments made to reconnect the basin are fully realized by returning fish populations.

Biologists don’t know exactly how quickly anadromous fish populations will respond to the dam removals and what unexpected challenges may arise. It is possible that populations will respond as they did for summer steelhead in the Elwha River – with immediate increases in adult spawners and the reemergence of life-history diversity. However, it is also possible that population increases will take some time as species seek out and reestablish themselves in habitat that has been inaccessible for a century.

Salmon, steelhead, and lamprey take 3-5 years to mature (depending on the species), so the first juveniles born in the upper Klamath won’t return as adults until several years after hatching. Additionally, population sizes for all species are relatively low today, meaning that some of the newly available habitat may not be used for several years. There may also be unexpected challenges that slow population increases, such as poor ocean conditions, drought, or passage bottlenecks at Upper Klamath Lake.

Without extensive and sustained monitoring, biologists will not have enough information to know if fish populations are increasing, what specific habitat is being utilized, and whether fisheries managers can adjust the reintroduction efforts to eliminate bottlenecks hindering population increases. In other words, biologists will have no ability to “adaptively manage” the reintroduction process if they do not have the information necessary to do so.

TU is committed to ensuring a successful Klamath watershed restoration. The Oregon and California reintroduction plans are comprehensive, science based, and well vetted, but they currently lack sustained and certain funding. A committed investment in monitoring serves as the basis for adaptively managing the reintroduction of native salmon, steelhead, and lamprey, and is critical to ensuring successful fish repopulation to the Klamath Basin. These important investments will also provide fundamental information to guide future dam removals and fish reintroduction efforts in other watersheds.

Reconnecting the Klamath has taken years of effort and represents hundreds of millions of dollars of investment. Soon, we will have the incredible opportunity to see native fishes on spawning gravel where they’ve been absent for over a century.

Dr. Haley Ohms is a Salmon Biologist on Trout Unlimited’s Science Team.

This post originally appeared on Trout Unlimited.