Extraordinary measures

TU and partners sue Pacific Gas and Electric to restore California’s third largest river and its legendary salmon and steelhead fisheries.

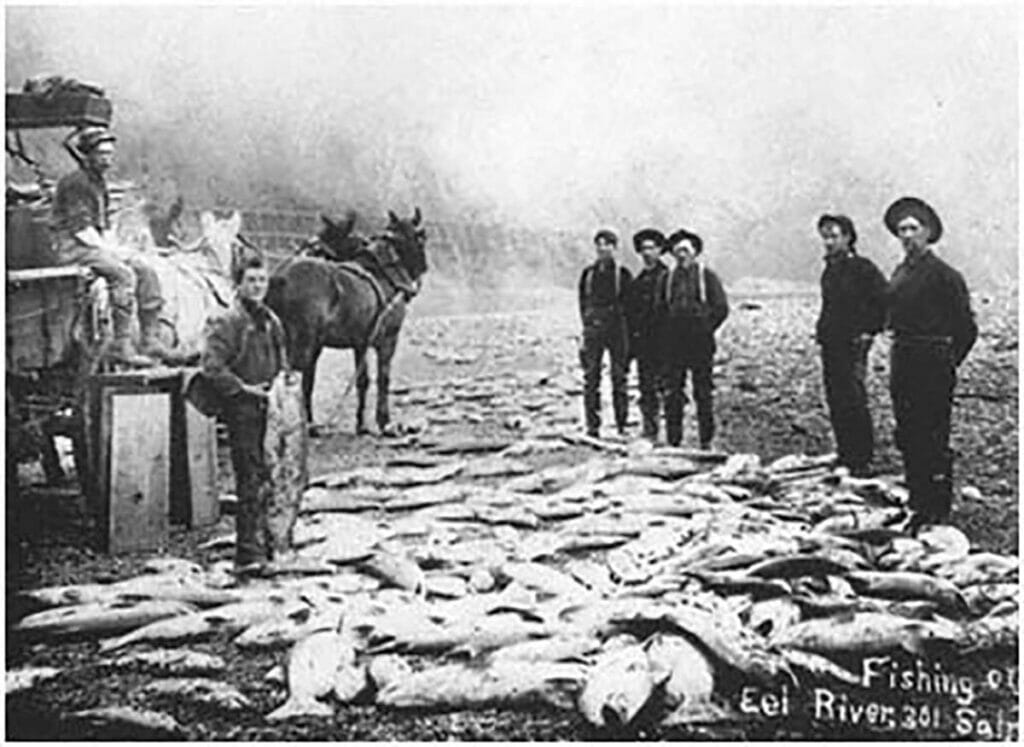

The Eel River, the beating heart of California’s Lost Coast, was historically one of the most productive rivers for salmon and steelhead in America. Today, however, the Eel’s anadromous fish populations are severely depressed – and its legendary fisheries are shadows of their former selves.

Eel River historical photo

Trout Unlimited (TU) is committed to restoring the Eel to its former glory. Over the past year, this commitment has taken the form of something TU almost never does – litigation – to capitalize on a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reduce impacts on salmon and steelhead and reconnect the lower river to its headwaters.

On May 17, TU joined with Friends of the Eel, California Trout, the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations, and the Institute for Fisheries Resources to file a lawsuit against Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) for causing illegal harm to listed salmon and steelhead populations in the Eel River under the Endangered Species Act.

Eel River fishing – photo credit Marcel Siegle

This lawsuit follows another TU and our Eel partners filed last summer against the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), for issuing a continuance of the operating license for PG&E’s Potter Valley Hydroelectric Project (PVP) without requiring changes in its operation recommended by federal fishery managers to reduce impacts on salmon, steelhead and Pacific lamprey.

Matt Clifford, director of law and policy for TU’s California program, says, “The closure of this year’s salmon fishery in California and southern Oregon because so few fish are forecast to return is a dire reminder that time is running out for native salmonids. If we want to have salmon and steelhead in our rivers and on our plates in the future, we must take extraordinary measures to help them today, especially in places like the Eel River, which arguably offers the biggest potential payoff for wild salmon and steelhead in all of California.”

***

The Potter Valley Project is one of the primary factors in the decline of salmon and steelhead in the Eel. The two dams of this project completely block fish passage to and from nearly 300 miles of cool waters and high-quality habitat in the headwaters.

Mainstem Eel River – photo credit Michael Weir, CalTrout

Yet thanks to some of the Eel’s waters being protected by special designations, and more than 20 years of restoration work TU’s North Coast Coho Project and others have done in the watershed, the Eel River remains perhaps California’s best hope for salvaging wild salmon and steelhead runs.

The key to restoring the Eel and its fisheries is to remove the PVP’s dams, Scott and Cape Horn.

In addition to killing Eel River salmon and steelhead, the PVP has been losing money for years. After months of waffling, PG&E has stated its intention to decommission the project and remove both dams. Until that happens, PG&E must continue to operate under successive one-year extensions of the operating license for the century-old water diversion project (which now produces no hydroelectric power) from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

Photo credit: Matt Clifford

Last year, however, the 20-year-old Biological Opinion (a formal analysis of effects on fish and wildlife) under which the PVP had been operating expired. NOAA Fisheries, the federal agency responsible for conserving salmon and steelhead stocks, informed PG&E that operation of the PVP was no longer covered by that Biological Opinion and formally recommended that PG&E implement a variety of changes in the project’s operations to reduce impacts on salmon, steelhead and Pacific lamprey species currently listed under the Endangered Species Act.

There is increasing pressure (including the results of a recent study on the vulnerability of the PVP to damage from seismic events) on PG&E to take out the Eel River dams. But until the dams are actually removed, their operation continues to subject fish to lethal water temperatures, block adult fish from reaching high-quality spawning and rearing habitat and prevent downstream migration of juvenile fish to the ocean.

The Eel’s wild salmon and steelhead runs – and the fisheries, communities and cultures that depend on them – are hanging on by a thread. So, when PG&E continued to reject our coalition’s requests to implement recommended changes in operation of the PVP to reduce harm to migratory fish, TU and our coalition partners took to the courts again and filed a lawsuit against PG&E over illegal take of listed salmon and steelhead populations under the Endangered Species Act.

Clifford noted that salmon and steelhead are dying and spawning poorly because they can’t pass the dams to reach cooler conditions in the headwaters of the Eel. He said, “While we appreciate PG&E’s stated intent to remove the two dams of the Potter Valley Project, we simply can’t afford the status quo for operating the project in the interim. PG&E needs to do the right thing here. Some relatively minor changes, such as operating that fish ladder differently and managing the cold-water pool behind Scott Dam more effectively, would go a long way toward reducing illegal take of listed species while we work through the decommissioning process.”

To read the press release that accompanied the filing of TU’s lawsuit against PG&E, go here. For more information about TU’s long-time efforts to restore the Eel and its salmon and steelhead runs, go here.

This post originally appeared on Trout Unlimited.