The Yuba River and the Bay Delta: A Vital Connection for Salmon

The Yuba River and the Bay Delta are connected by more than water. They are also linked by the migration of salmon, which depend on both habitats for their survival. These fish provide food, recreation, and cultural value for millions of Californians.

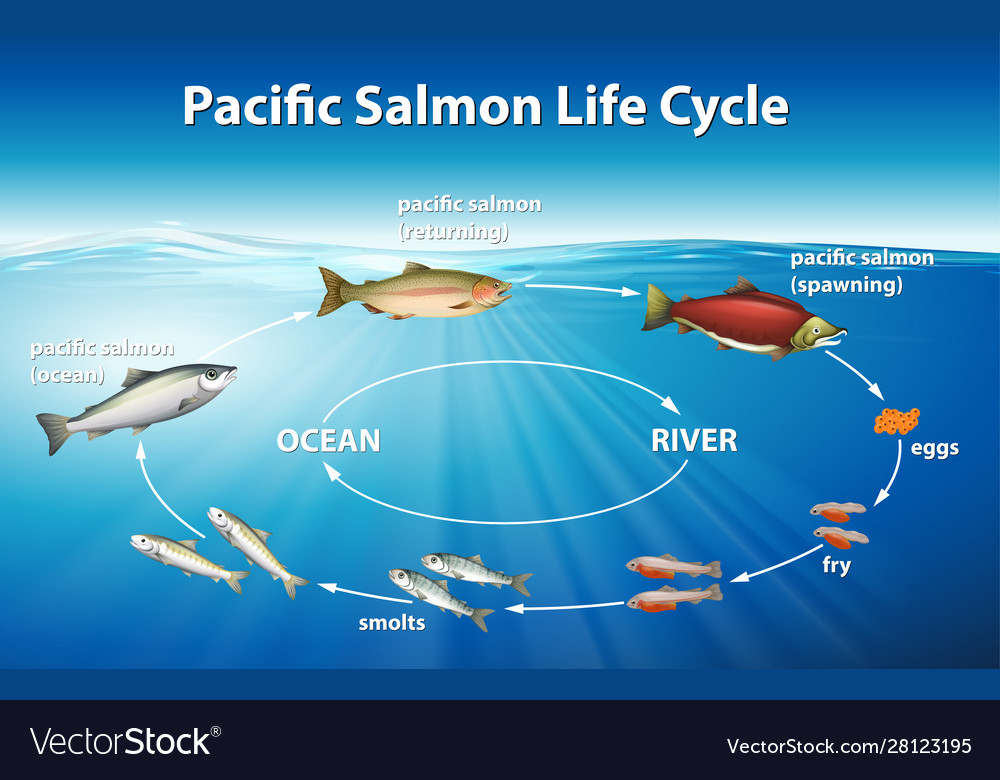

The spring-run Chinook salmon’s life cycle is an extraordinary odyssey that begins and concludes in Central Valley streams such as the Yuba River. Once the most abundant run in California, Spring-run Chinook salmon are now listed as threatened on the federal and California state levels. This article will guide you through their life stages, spotlight key elements like temperature, nursery habitats, and water flow, as well as highlight their duration in various locales and the obstacles they encounter along the way.

Spawning in the Yuba River

The journey of the spring-run Chinook salmon commences as they migrate past the Golden Gate in January-February and arrive at their native spawning ground in the Spring, where they then hold in deep, cold pools over Summer. They will begin spawning in the Yuba River’s chilly, pebbly stretches when the water temperature drops to 42-55 degrees Fahrenheit.

The lifecycle starts when nests (or redds) are built as female salmon choose a specific gravel area with shallow but fast-moving water that supplies steady oxygen to eggs as they incubate. The size of the gravel is very important, as it must be small enough for the female salmon to move with her tail but large enough to allow water flow and not suffocate the buried eggs.

Salmon follow their instincts to move upstream in search of the most suitable spawning grounds, but nowadays they are often met with towering, impassable dams. These dams not only block water from moving downstream, but they also starve the river of spawning gravels by preventing the natural replenishment of material.

On the Yuba River, Englebright Dam blocks over 80% of historic salmon habitat in the upper watershed. A large portion of spawning activity observed in the Yuba occurs in the stretch between Englebright Dam and the Narrows in gravel that is placed there by the Army Corps of Engineers as part of required mitigation for the harm caused by the dam. Spawning gravels lower in the Yuba River a continuously replenished by the hydraulic mining debris of the Yuba Goldfields.

The eggs are deposited and fertilized from August through as late as October, experiencing some overlap with the Yuba’s fall-run Chinook salmon. Embryos mature throughout the winter, nestled within the riverbed’s gravel.

Nursery Habitat and Water Currents

Post-hatching, the alevins (freshly hatched salmon) stay within the gravel, drawing nourishment from their yolk sacs. As they progress into fry, they emerge from their redds and seek specific nursery (aka rearing) habitats with sufficient supplies of clean, cold water and food. Juvenile salmon feed on benthic macroinvertebrates (BMIs), which also rely on high-quality, cold water for survival.

Cover from predators and places to hide from high velocity river flows are also key elements to optimal rearing conditions for these juvenile salmon. These conditions are often found in off-channel habitats such as side channels, alcoves, and floodplain features that largely have, unfortunately, been disconnected due to historic mining activity on the Yuba.

Higher water flows from springtime rain and snowmelt are important cues for triggering salmon downstream migration. However, spring-run can express different patterns in outmigration timing. Early migrants may leave the system as soon as January, and others may begin to out-migrate as late as June. A rare but important few may spend an entire year rearing in their natal stream and leave the following spring with the next generation of juveniles.

Studies have shown that juveniles that decide to over-summer are more likely to return as adults to spawn. On the Yuba, temperatures tend to remain cold enough throughout the year to support all strategies in downstream migration timing. Having a diverse portfolio in life history expression is important to maintaining resiliency in a changing climate.

Support SYRCL’s Efforts to Save the Salmon

If you would like to support SYRCL’s efforts to save salmon, restore salmon habitat, or educate local students about the salmon life-cycle along the lower Yuba, please donate today. All gifts made by December 31 will be matched by a generous donor who cares about the Yuba and preparing a new generation of river and salmon advocates.

Voyage to the Delta and Bay

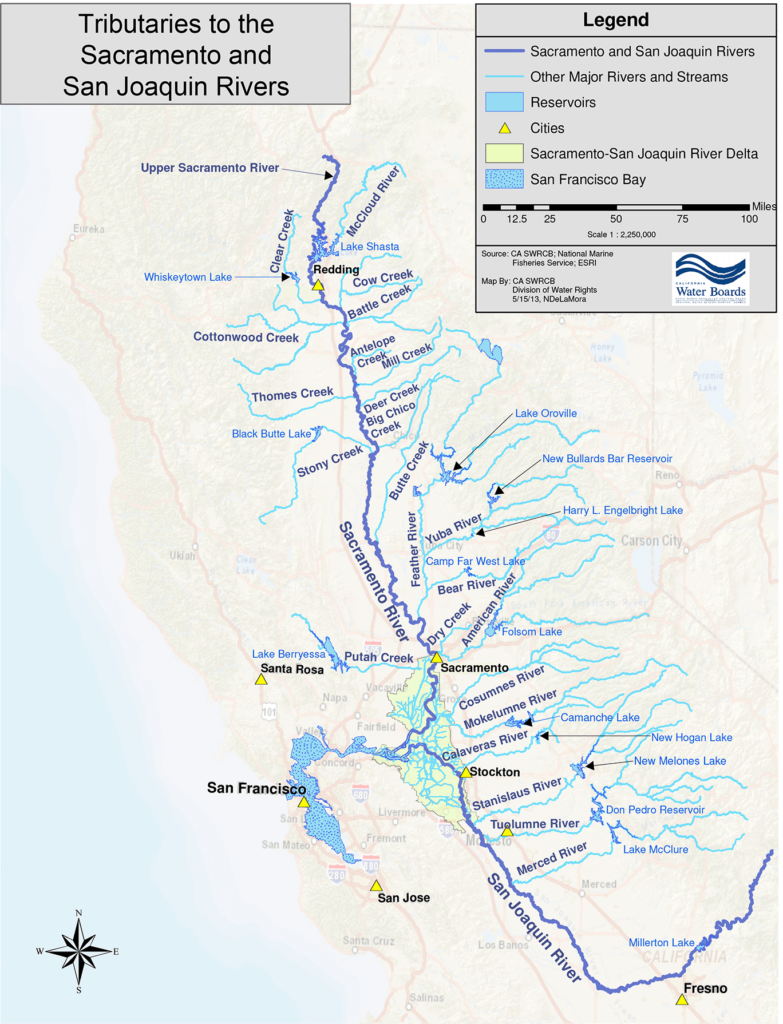

Next, juvenile Chinook embark on their 110-mile descent downstream towards the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta. This estuarine area acts as a pivotal transitional space where they adjust to saline water and gear up for life in the ocean in a process called smoltification.

Smolts might linger in estuaries from a few days to multiple weeks, foraging and acclimating to the altered environment. This is a very dangerous time for these young salmon, as they face a gauntlet of obstacles including non-native predators, water diversion infrastructure, and potentially stressful or deadly warm water temperatures. Survival during this relatively short period of time in a salmon’s life cycle is low and even lower during drought years.

Oceanic Existence

The Yuba salmon then venture into the Pacific Ocean, where their success is highly influenced by the timing and availability of ocean nutrients powered by the process of ocean upwelling. Salmon mature and grow for one to seven years, but typically only two. During this period, they feed on smaller fish and accumulate important marine-derived nutrients in their fatty tissues. Because of the vastness of the ocean, salmon are much less studied during this time in their life cycle. Once reproductively mature, they will once again begin an epic journey- this time, back home.

Homeward Bound

Upon maturing, the salmon undertake the strenuous return to their natal Yuba River to spawn, thus fulfilling their life cycle. They traverse through the Delta and Bay, once again facing the same obstacles they did as juveniles, but this time with size and strength on their side. During their journey, they no longer feed and subsist only on their fatty reserves. Once they have completed their reproductive mission, the salmon die and return the nutrients of their body to the ecosystem providing the critical ocean derived nutrients that feed the BMIs their fry will eat.

Spawning and Conclusion

Safeguarding salmon’s habitats and maintaining the necessary water currents for their various life stages is crucial for their ongoing survival.

This piece offers a brief look into the intricate and interlinked phases of the spring-run salmon’s life cycle, underscoring the significance of each stage and the adversities they face throughout their journey from the Yuba to the Bay Delta and back home again.

This is our second piece in a series highlighting the Yuba and Bay Delta connection. To see more, visit:

If you would like to support SYRCL’s efforts to save salmon, restore salmon habitat, or educate local students about the salmon life-cycle along the lower Yuba, please donate today. All gifts made by December 31 will be matched by a generous donor who cares about the Yuba and preparing a new generation of river and salmon advocates.

This post originally appeared on SYRCL.