Planning for the Klamath dams to come down

TU partners with NOAA to prioritize high-impact restoration projects in anticipation of salmon returning

After decades of advocacy and work by a dedicated coalition of tribes, conservationists, anglers, and commercial fisherman, four dams on the lower Klamath River are finally coming down. Removing these barriers will improve water quality, greatly reduce the disease outbreaks killing adult and juvenile fish, and allow salmon and steelhead to regain access to over 400 miles of habitat that has been blocked for over a century.

It is the largest river restoration project in history.

The long-awaited return of steelhead, coho and Chinook salmon, and other native species, puts important attention on the habitat that will become available to these struggling populations once again. To rebuild their numbers and reestablish populations above the former dam sites, the fish require dependable supplies of cold, clean water and intact, connected spawning and rearing habitat. Above and below the dams, habitat restoration work has been underway for years, but now there is new urgency and opportunity to restore key habitat in the portion of the watershed where the four large dams and their accompanying impoundments inundated the landscape and blocked migration. This section of the basin is commonly referred to as the “reservoir reach” of the river.

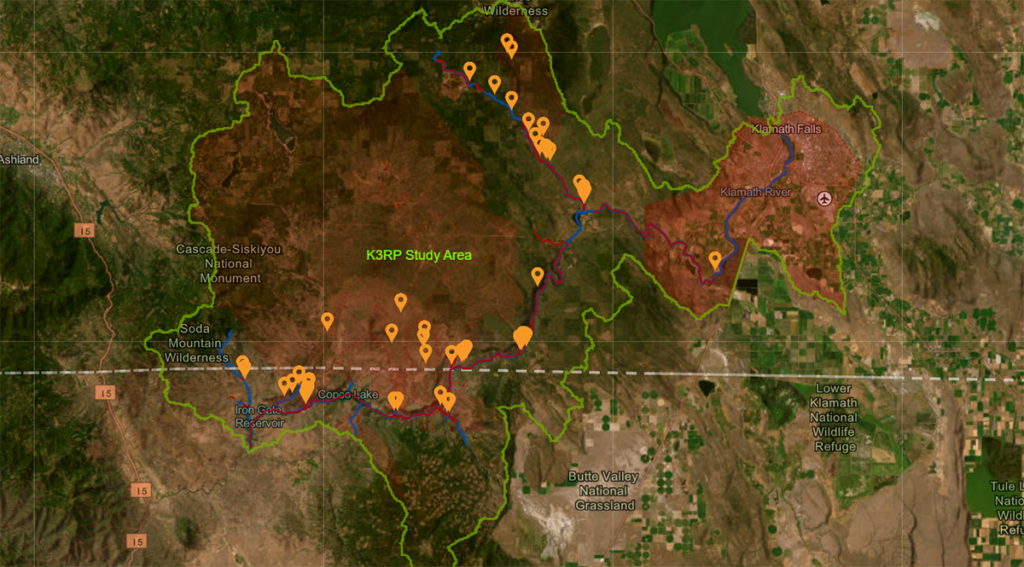

To facilitate a strategic and efficient approach to this critical work, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Restoration Center partnered with Trout Unlimited and the Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission (PSMFC) to produce a comprehensive report identifying and prioritizing the most impactful restoration projects within the reservoir reach of the Klamath. After two years of work, the Klamath River Reservoir Reach Restoration Plan has been finalized and was released last week.

The announcement from NOAA Fisheries is available on their blog.

The restoration plan, including detailed appendices and maps, is available to collaborators in the basin and the public at a website hosted by PSMFC.

Klamath River Reservoir Reach Restoration Plan

Nell Scott directs TU’s restoration work in the Upper Klamath Basin. She and her team worked closely with NOAA and PSMFC staff to produce the new report. We reached out to her for insights into the scope and implications of this new resource guiding habitat restoration in this key section of the Klamath basin.

TU: Nell, can you describe the location and size of the reservoir reach on the Klamath?

Nell Scott: The Klamath River watershed is very large and spans southern Oregon and northern California. The reservoir reach is a 63-mile-long section of the river flowing from Link River Dam to Iron Gate Dam. It is currently impacted by six dams (four of which are slated for removal). Aside from 63 miles of mainstem habitat, this section also includes almost 40 miles of key tributary habitat, including Spencer Creek, Shovel Creek, and Jenny Creek.

The first dam, Copco 2, is scheduled to be removed next summer. Three other large dams – JC Boyle, Copco No. 1, and Iron Gate – will be removed during the summer of 2024. When that happens, fish will regain access to a huge portion of the Klamath watershed, including the reservoir reach. Our job, and the goal of this report, is to make sure this section of the watershed is ready for them.

In particular, we expect this area of the river to be especially important for Coho salmon, as their historic range likely only extended upstream to Spencer Creek. The reservoir reach will certainly be important for steelhead and Chinook as well, but those fish are also expected to recolonize much higher in the system.

TU: Can you tell us a bit about how the new report came together and its key recommendations?

Nell Scott: Everyone working on restoration in the basin recognizes a need to prioritize the most impactful habitat and water quality projects in the reservoir reach. And to get that work done as soon as possible so the fish can take full advantage of the habitat available right away.

This report took two years to pull together, a remarkably fast turnaround considering the scope of the work, but also a sign of how important of a project this was to all the contributors. NOAA funded and guided the process and convened a Science Panel and a Technical Advisory Committee to evaluate methods and protocols and help prioritization of projects. PSMFC was tasked with on-the-ground identification of fish passage, flood plain reconnection, and other habitat projects, as well as detailed GIS analyses. They also built and will host the online home of the final report. TU worked to identify key cold water resources, flow restoration opportunities, opportunities to improve water quality, and critical fish screening needs to keep fish from getting trapped in irrigation diversions.

In the end, the report identified over 80 potential habitat and fish passage restoration opportunities, nearly 80 potential locations for screening irrigation diversions, and almost 40 projects that would benefit instream flows within the reservoir reach. It then evaluates potential impacts to fish recovery and rates each of these projects as high, medium, or low priority. We expect this plan to be a tool for conservation partners to engage and partner with private landowners in the reach to accomplish restoration goals.

NOAA and PSMFC were both deeply committed to the work and exceptional to work with.

TU: With dam removal moving forward, and the timely arrival of this restoration plan, what are the next steps required to start moving ahead with on-the-ground work within the reservoir reach?

Nell Scott: The report gives all the organizations, agencies, tribes, and landowners working on restoration efforts in the basin a fairly specific roadmap. Now that we know what work needs to be accomplished, everyone needs to begin landowner outreach, evaluate project feasibility, quickly leverage funding, and design and implement projects.

All of this takes time, but as we’ve discussed, there is real urgency and momentum to keep moving as fast as possible because the dams are coming down and fish will be returning very, very soon.

To that end, as the report was being finalized, I reached out to a number of stakeholders in the basin to start a collaborative discussion of next steps. There are a large number of tribes, agencies, conservation groups, and landowners all doing important restoration work in the basin. Each has areas of expertise, existing relationships, and specific scopes of work. There is a recognized need for all of us to be more aware of each other’s work to make sure we leverage partnerships whenever possible.

TU: That sounds great. How did that meeting go?

Nell Scott: Honestly, it was exciting and inspiring. We had a large number of groups participate and have already identified and reached out to many more groups that should be added to the collaboration for our next meeting in early 2023. There is a great deal of work that needs to be done, but I think there is a widespread understanding that the opportunity in the Klamath basin is historic and monumental. No one could do it all alone, we need new levels of transparency and coordination to make it efficient and effective.

The report gives us our ecological priorities. Now we need to see where projects have already begun, and how to best divide up the rest of the work. No one wants to just do the easy projects. Everyone working in the basin wants to see the most impactful work get done, because everyone wants to see these fish returning to the best habitat and water resources possible.

This post originally appeared on Trout Unlimited.