It Snowed – Is The Colorado River Saved?

With the substantial amount of snow that has fallen across the Colorado River basin over the past couple of months, I have been asked many questions about the state of the drought, and whether all this precipitation will reverse the severe declines in both Lake Powell and Lake Mead. Will all this snow “save” the Colorado River basin from further declines and cutbacks? Can we all just go back to normal now and not worry about conservation so much?

Spoiler alert – Not likely.

Certainly, all this snow will help quench the basin’s immediate thirst. It may also serve to have much of the basin delay confronting what has been shaping up to be a real emergency, with real consequences for everyone who relies on the Colorado River – but not for long. If we experience another low snowpack year which has been predicted, the situation from the top of the basin to Mexico will be pretty dire – and if this recent snow funnel turns off, it still could be. But for now, it appears that, while the current snow conditions will certainly not save the day, they might help side-step having to immediately endure worst-case scenarios beginning as early as this spring, which hopefully can provide the states and Federal government some space to come together and bring the rest of the Colorado River community along in support of workable solutions for the basin by the end of the summer.

Through my role with American Rivers, I am honored to be one of the two Environmental Representatives on the Glen Canyon Dam Adaptive Management Program (GCD-AMP) Technical Work Group (TWG) which is intimately involved with much of the science conducted in the Grand Canyon and Lake Powell. As part of that role, how Glen Canyon Dam operates and is managed is of central consideration, and the impacts of decisions around how water flows through the dam are of critical importance to the ecological, recreational, and cultural values of the Grand Canyon and the overall natural heritage it provides.

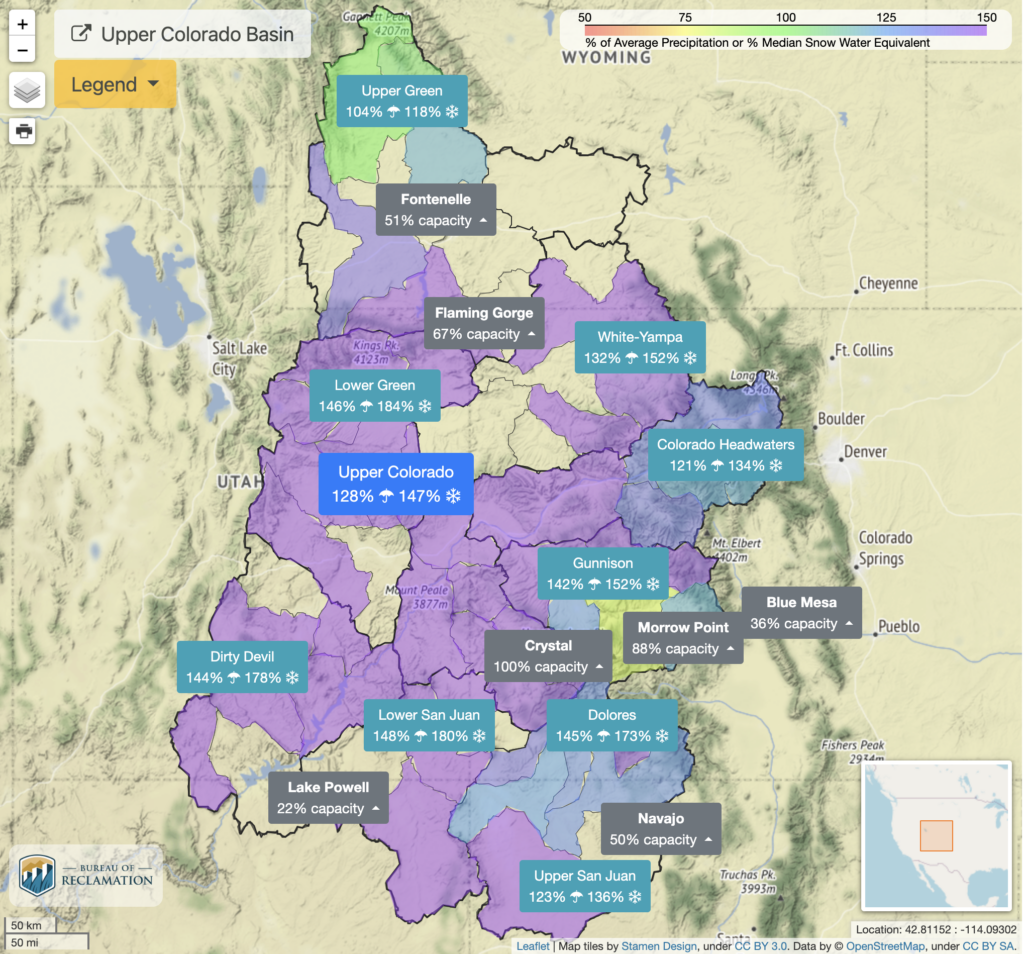

Last week, at a meeting in Phoenix, we got detailed readouts around the hydrologic conditions in the Upper Basin of the Colorado River (Colorado, Wyoming, Utah, and New Mexico make up the Upper Basin) and so far, the data looks positive for this current water year.

All those purple and blue blobs are great news and something to cheer about. These numbers all play into how the Bureau of Reclamation (BOR), the Federal agency that oversees and manages the federal infrastructure for the Colorado River system, forecasts likely water supply scenarios in different areas of the basin. But for the time being, let’s stick with Glen Canyon Dam and Lake Powell.

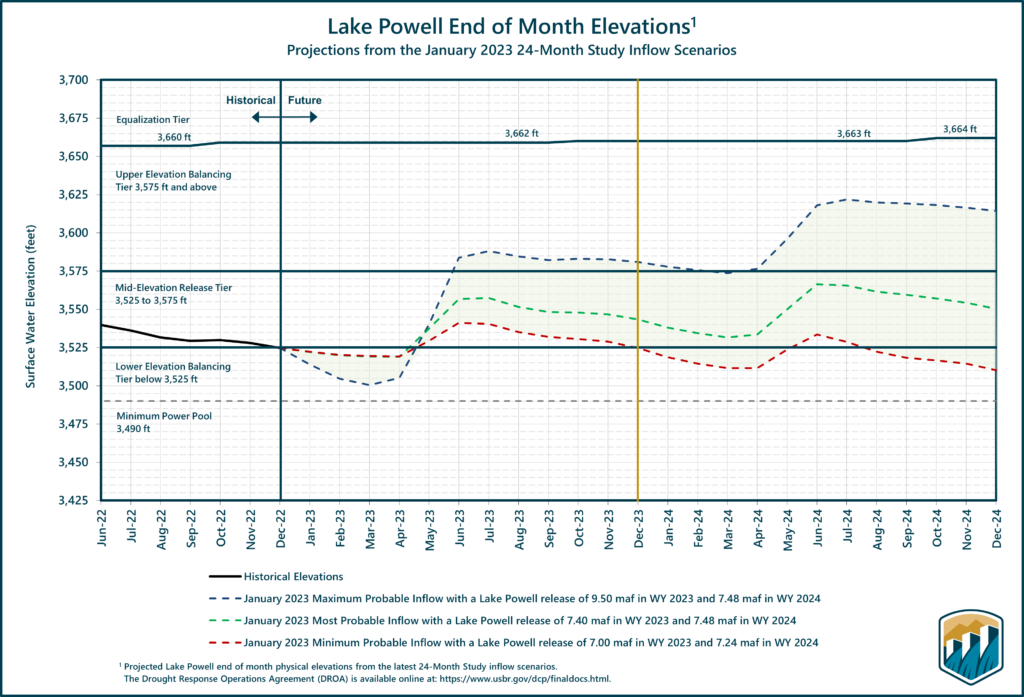

The chart above may look confusing but bear with me. The vertical axis is the elevation of the water stored behind Glen Canyon Dam in Lake Powell. The horizontal axis is time, looking ahead across the next two years. Modeling experts at BOR run dozens of simulations based on 30-year average hydrology, current snowpack conditions, soil moisture, projected meteorology, and water use estimates to identify potential probabilities around how much water may be coming through the system, including how much water may reasonably be expected to flow into Lake Powell in a given year. Then, understanding these “inflows” projections in combination with other resource considerations, the BOR projects the volume and timing of water to be released out of Lake Powell, through the Grand Canyon, and into Lake Mead on an annual basis.

If you look carefully at the chart above, you will see three dotted lines undulating from left to right. Those three lines are the “Minimum, Maximum, and Most” probable storage scenarios for Lake Powell based on different inflow and other inputs (Maximum being the top, a blue line which reflects where 90% of the scenarios will land at or below in storage elevation, meaning the maximum probable amount of water to be stored at Lake Powell for the relevant year; Minimum being the bottom, red line which reflects where 10% of the scenarios will land or fall below in storage elevation, meaning the minimum probable amount of water to be stored at Lake Powell for the relevant year; and, Most being the middle, green line, which reflects that 50% of the scenarios are likely to be at or below in Lake Powell storage elevations for the year. Each of these projections is based on CURRENT conditions and is subject to change as we learn more about actual, as opposed to modeled, conditions in the basin.

As you can see, the line trends down from now until about mid-April 2023, then makes a sharp curve upwards. This represents spring runoff – it is current, frozen snow (very low runoff in the rivers) transitioning into spring (lots of snowpack melting and the rivers flowing vigorously.) Then as we get into summer and fall, things more or less flatten out as the snowpack depletes and levels in Lake Powell stabilize.

The most important line on the chart above (at least for this blog) is the bottom line (Minimum Probable,) and, in particular, the April 2024 timeframe, the lowest point on the chart. Below that lowest point is a grey dashed line marked “Minimum Power Pool – 3,490ft.” This represents the elevation where Lake Powell can no longer produce any hydropower electricity because the water has fallen too low to turn the turbines.

Just a couple of months ago, it looked like Lake Powell may fall below that Minimum Power Pool elevation sometime around the April 2024 timeframe, and if this winter’s snowpack was dismal, the threat to the minimum power pool could be much higher much sooner. Last fall, BOR Commissioner Touton instructed that the Basin must come up with an additional 2- and 4-million-acre feet of Colorado River water to avoid critical threats to infrastructure and the system between now and the time new long-term operating criteria can be finalized (est. 2026). This directive, along with several other factors, also inspired BOR to consider partially modifying the current operating criteria through a process called a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS).

A SEIS is, in essence, a comprehensive study around some options that could guide operations at the Glen Canyon Dam and other facilities to forestall threats to the health, safety, and continuing functionality of the system until more comprehensive management plans can be assessed and considered. Short-term adjustments to system operations will likely consider, among other things, the release of less water (and potentially MUCH less water) from Lake Powell in the current and next years with the assumption that storage at Lake Powell could continue to decline. That study is in process, but we all need to continue to press the urgency of this situation and find every way possible to reduce the consumption of Colorado River water, from every user across the entire basin. Just because the snowpack looks good today, doesn’t reduce the immediate need to find a way to live within the means that the river can provide starting now.

Now, some caveats to all this optimism. First, it could stop snowing, like it did last year, and this trend of piles of happy snow could go away. Second, the basin overall is in a serious water deficit across nearly all reservoirs in the Upper Basin. BOR has had to release a lot of water over the past two years under emergency and drought contingency actions, including the implementation of a Drought Response Operations Agreement to try to keep Lake Powell from falling even farther and even faster. Lastly, runoff matters, and the combination of how soon spring arrives and how warm it gets, combined with how moist the soil is as that snow begins to melt will dictate how much water makes its journey down the river. With the solid monsoon seasons over the past two summers, the soil moisture is much better than it was a couple of years ago. But dry soils absorb water as the snow melts, and if the soils are too dry, runoff water never makes it to the rivers in the first place. In fact, many believe that relying on the 30-year average hydrology conditions in the basin as part of the modeling foundation leads to potentially overly optimistic results in storage conditions.

So, there is cause for optimism, and cause for skepticism, but at least at this point in early 2023, things are looking as good as they likely could to provide a little room to keep working toward collaborative solutions than in years past. Keep those snow dances coming!