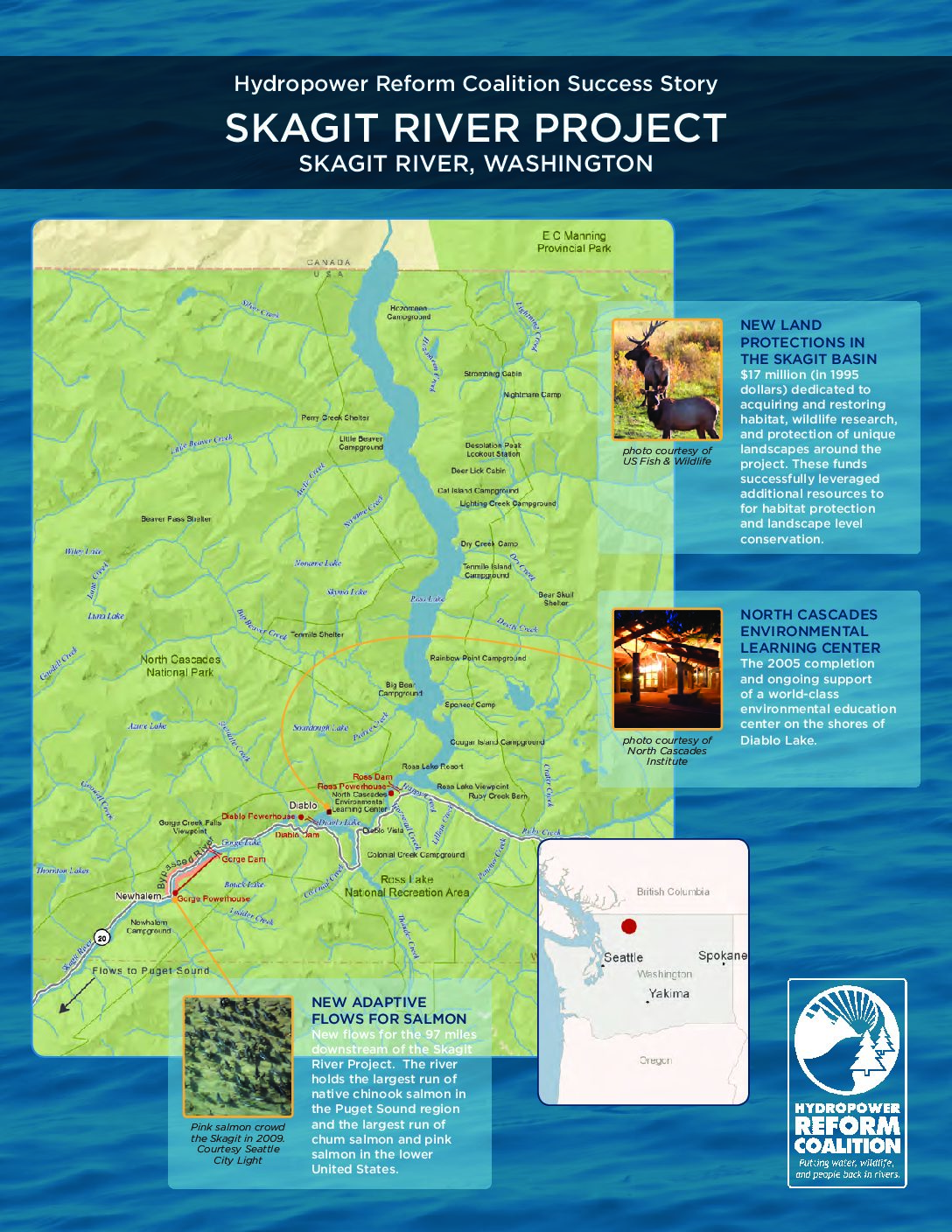

The Skagit River basin is the largest drainage in Puget Sound, covering 3,140 square miles and representing a unique regional and national resource. Over 158 miles of river including its major tributaries are federally protected Wild and Scenic reaches. Its upper watershed is deeply embedded in the spectacular North Cascades National Park [pictured at right]. Within the Park, the Ross Lake National Recreation Area immediately surrounds 35 miles of Skagit River, surrounding Seattle City Light’s hydroelectric project.

At the threshold of the public power era, Seattle City Light developed the Skagit River Project, a three-dam hydropower project on the upper Skagit River. In 1926, City Light built the first Skagit River dam, Gorge Dam. Slightly upstream and the second to be constructed, Diablo Dam was the highest dam in the world at the time of its completion in 1930. Finally and farthest upstream, Ross Dam was completed in 1949, creating a 24-mile reservoir that extends 1.5 miles over the Canadian border. On average, Ross Lake is more than a mile wide. None of the Skagit dams has fish passage facilities. Scientific studies show that the Gorge Reach of the Skagit was the highest point salmon could historically reach. Downstream of these dams, the Skagit is unimpeded.

Beginning in 1968, Seattle City Light publicly planned changes to the Skagit River Project, including raising the height of Ross Dam from 540 feet to 665 feet (see sidebar). As its 1927 license was set to expire, City Light filed for a new license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) in 1977. At the same time, FERC initiated a separate proceeding to adjust dam releases and avoid an irreversible decline of the Skagit salmon stocks. The result of this proceeding was the 1981 Skagit Fisheries Agreement. The Agreement rewrote the flow regime for the lower 97 miles of the Skagit, improving conditions for salmon and setting the stage for licensing negotiations.

The Skagit compromise was a precedent-setting effort. In 1991, Seattle City Light filed a comprehensive set of settlement agreements addressing all environmental issues at the project. Cultural settlements with tribes were filed in 1993. FERC ultimately accepted all of the settlements into a new license, effective in 1995. At that time, a comprehensive suite of settlements resolving all issues with all parties was a novel approach to hydropower licensing.

As a part of the Fisheries Agreement, flows from Gorge Powerhouse were modified with a focus on the 25 miles immediately downstream of the powerhouse. This reach holds the largest number of spawning chinook salmon, chum salmon, and pink salmon in the basin. Seattle City Light must ramp down its generating flows, rather than drop the river level suddenly. It also must steadily release minimum flows that are 150% higher than previous minimums, varying seasonally and annually to reflect more natural conditions. Throughout the period of the license, Seattle City Light must test the response of fish populations and the habitat availability for spawning and rearing under the new flows, and make ongoing changes to protect Skagit River salmon.

Under the settlement, Seattle City Light contributed to the construction and operations of the North Cascades Environmental Learning Center. Opened in 2005, the Center occupies a portion of the site of the old Diablo Lake Resort. Today the Center provides a home for the North Cascades Institute, dedicated to environmental education and connecting people to the landscape and ecology of the North Cascades.

To mitigate for the project’s footprint, City Light dedicated $17 million to land acquisition and management in order to offset the impact of the project on wildlife habitat in the Skagit River watershed, in particular eagle and elk habitat. As of 2008, ninety-four percent of the fund has been spent, and over 8,260 acres have been acquired. Half of this acreage is in the Skagit and Sauk River watersheds. The other half is in the South Fork Nooksack River watershed, a precedent- setting example of using mitigation funds to invest in habitat in a nearby watershed as high-value mitigation for habitat lost to hydropower development.

HRC or member-contributed

HRC or member-contributed