What happens to fish populations when dams are removed?

In 2014, the final pieces of two dams on the Elwha River in Washington were removed. The famous river restoration and fish recovery story was decades in the making and culminated in what is now a free-flowing Elwha from its source high in Olympic National Park to the sea. The river became a living laboratory of what happens when dams are breached and salmon have access to historic habitat once more.

Dams block or hamper not only fish migrations, but also the transport of sediment and wood that is crucial in maintaining river connectivity and diverse habitat structure. River flow is also drastically slowed in the reservoirs behind dams, which inundate habitat and create degraded environments with poor water quality.

Fish rely on river flow to guide them and become disoriented in the stagnant backwaters behind dams. Idaho’s juvenile salmon migrate passively, tail first out to ocean, a journey that once took a matter of days, but now takes weeks in the slow current behind eight dams along the Columbia-Snake river. Unquestionably, dams have done severe damage to rivers and native fish and wildlife populations that rely on connected, free-flowing watercourses.

Since 1912, 1,797 dams have been removed on rivers and streams across the United States.

Just as surely as the presence of dams degrades rivers, dam removal is the most effective way to restore river systems and bring fish populations back from near extinction. The necessity of migration and urge to recolonize formerly blocked habitat is baked into the DNA of our native fish, whether it be salmon and steelhead in the Columbia Basin, or river herring along the Eastern seaboard.

One of the key motives for dam removal is to restore or aid fish populations. In cases of dam removal, what actually happens to fish populations? How do fish populations respond to a restored habitat? Has a native fish population ever responded negatively to a restored, free-flowing river?

In the conversation surrounding the removal of the Lower Snake River Dams – which would be the largest river restoration project in history – this is an important question, and there are ample case studies that demonstrate how a river and its fish populations respond to dam removal.

The Edwards and Fort Halifax dams were removed on the Kennebec River in Maine in the early 2000’s. Alewives, a type of herring, numbered only 78,000 in 1999 just before the first dam was removed. In 2018 the alewife run topped 5.5 million fish.

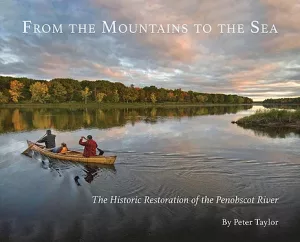

Also in Maine, two dams were removed on the Penobscot River. Once bypass is completed on a third, over 1,000 miles of river habitat will be reopened to native fish. The river’s sea-run or ‘anadromous’ fish populations have together increased from 2,331 in 2009 to 2.1 million in 2020.

In the Northwest, the White Salmon River’s Condit Dam was removed a decade ago. After the initial flush of sediment that accompanies dam breaching, fish have started to come back. Juvenile Chinook and coho have been surveyed in every accessible tributary upstream of the old dam-site.

As for the Elwha, native salmon and steelhead are busy recolonizing 70 miles of prime river habitat. 7,600 Chinook returned to the river in 2019, the most since the late 1980’s. Amazingly, summer steelhead that were presumed to be extinct in the river have returned to its upper reaches, seeded from rainbow trout populations that had been blocked off for over 100 years from downstream habitat.

Once a dam is removed, a river’s path towards restoration is sinuous and winding with many surprises along the way. The recovery of native fish to pre-dam levels takes time, and populations gradually rebuild over the course of multiple fish generations. That being said, there has never been a dam removal that has not seen fish populations in the river bounce back.

The rhetoric around Lower Snake River dam removal from supporters of the status quo has at times included uncertainty around just how good for salmon removing dams would be. The science and previous case studies are clear – not only is dam removal the only viable solution for population recovery, it is a necessity if we are to prevent our wild salmon and steelhead from going extinct.

IRU continues to support a comprehensive regional package for salmon recovery that includes Lower Snake River restoration via dam breaching as well as renewable energy and transportation infrastructure development. Congressman Mike Simpson has proposed such a framework, that invests in the Northwest’s future and would effectively recover our wild salmon and steelhead to abundance. Members of Congress across the region, as well as the Biden Administration now must come together with decisive action.